New Opportunities in Critical Blue Carbon Ecosystems in Geoparks

Harnessing the Climate and Community Potential of Mangroves, Seagrasses, and Saltmarshes in Protected Geopark Landscapes

INSIGHTCLIMATE CHANGE AND SUSTAINABILITYNATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS

New Opportunities in Critical Blue Carbon Ecosystems in Geoparks

Blue Carbon ecosystems within Indonesia's geopark sites can offer strong potential to support the core goal of UNESCO Global Geoparks: empowering local communities. Local involvement in preserving these ecosystems adds value by ensuring that blue carbon potential is maximized through the integration of local wisdom, research and technology, and sustainable economic practices—strengthening economic resilience amid climate change challenges. Preserving the environment and blue ecosystem aligns with achieving the main goals and purposes of global geoparks.

Can We Take This as an Opportunity for Indonesian Geoparks?

“Celebrating Earth Heritage and Sustaining Local Communities” is the core mission of the Global Geopark framework. In a more comprehensive way, preserving geological heritage within geoparks goes beyond merely showcasing landscapes—it also encompasses the meaningful utilization of these natural legacies for sustainability and community well-being.

To achieve the goal of sustaining local communities, geoparks must function as integrated systems that combine the three inseparable pillars: education, conservation, and sustainable economic development. These pillars, when implemented as a unified framework, empower geopark management boards to achieve the 16 development focus areas set by UNESCO effectively and inclusively.

Indonesia's success in achieving 12 UNESCO Global Geopark (UGGp) designations reflects the country’s strong commitment and enthusiasm toward the geopark concept. Quantitatively speaking, Indonesia leads ASEAN in the number of designated UGGps, outpacing Thailand and Malaysia (each with two UGGps) and the Philippines (with one). However, a critical reflection is necessary: does the growth in number correlate with quality improvements and impactful community-based initiatives? This remains a challenge that must be addressed through measurable, inclusive, and sustainable strategies.

As an archipelagic nation, Indonesia's geoparks are naturally endowed with rich coastal and small island ecosystems. Many of these geopark sites contain blue carbon ecosystems—such as mangroves, seagrass meadows, and tidal marshes—which have the capacity to store carbon up to 35 times more than terrestrial forests. This exceptional ecological function presents a strategic advantage.

Therefore, integrating blue carbon development into the geopark agenda is not merely an environmental imperative—it is a socioeconomic opportunity. When managed with local participation, scientific research, and climate-smart economic models, blue carbon ecosystems can become key drivers of community-based climate resilience and sustainable income generation. In this context, geoparks in Indonesia are uniquely positioned to lead as living laboratories of climate action and inclusive economic growth.

“Celebrating Earth Heritage and Sustaining Local Communities” is the core mission of the Global Geopark framework. In a more comprehensive way, preserving geological heritage within geoparks goes beyond merely showcasing landscapes—it also encompasses the meaningful utilization of these natural legacies for sustainability and community well-being.

To achieve the goal of sustaining local communities, geoparks must function as integrated systems that combine the three inseparable pillars: education, conservation, and sustainable economic development. These pillars, when implemented as a unified framework, empower geopark management boards to achieve the 16 development focus areas set by UNESCO effectively and inclusively.

Indonesia's success in achieving 12 UNESCO Global Geopark (UGGp) designations reflects the country’s strong commitment and enthusiasm toward the geopark concept. Quantitatively speaking, Indonesia leads ASEAN in the number of designated UGGps, outpacing Thailand and Malaysia (each with two UGGps) and the Philippines (with one). However, a critical reflection is necessary: does the growth in number correlate with quality improvements and impactful community-based initiatives? This remains a challenge that must be addressed through measurable, inclusive, and sustainable strategies.

As an archipelagic nation, Indonesia's geoparks are naturally endowed with rich coastal and small island ecosystems. Many of these geopark sites contain blue carbon ecosystems—such as mangroves, seagrass meadows, and tidal marshes—which have the capacity to store carbon up to 35 times more than terrestrial forests. This exceptional ecological function presents a strategic advantage.

Therefore, integrating blue carbon development into the geopark agenda is not merely an environmental imperative—it is a socioeconomic opportunity. When managed with local participation, scientific research, and climate-smart economic models, blue carbon ecosystems can become key drivers of community-based climate resilience and sustainable income generation. In this context, geoparks in Indonesia are uniquely positioned to lead as living laboratories of climate action and inclusive economic growth.

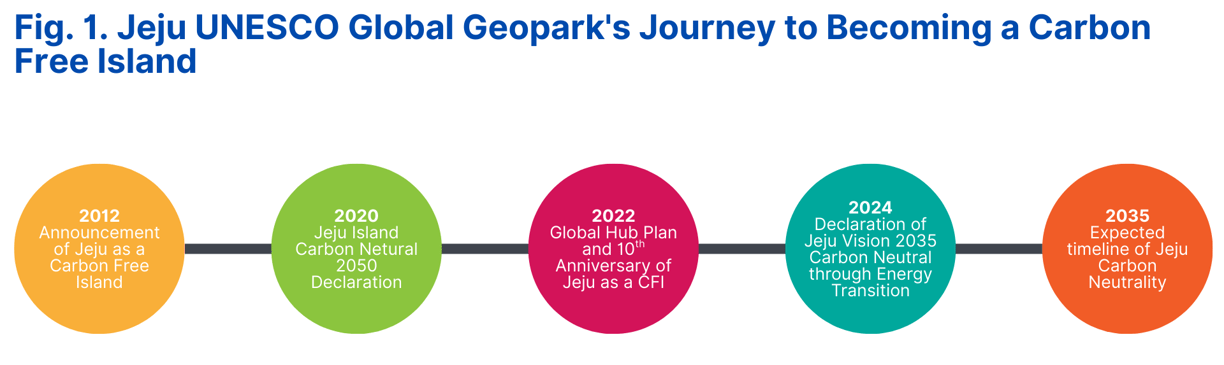

Lessons Learned from Jeju UNESCO Global Geopark: A Study Case for Low Carbon Geopark Development

Jeju Island is a geopark island situated in the Republic of Korea. In addition to being recognized as a UNESCO Global Geopark, Jeju is the only place in the world to have earned three designations from UNESCO: a Biosphere Reserve (2002), a World Natural Heritage Site (2007), and a Global Geopark (2010). With an area of 1,849 km² and a population of 672,948, Jeju has a population density of approximately 364 people per km², making it the most densely populated island in Korea.

Despite challenges related to population density and increasing tourist numbers, Jeju has demonstrated a strong commitment to addressing environmental issues. Through its ambitious Carbon Free Island (CFI) 2030 initiative, Jeju has set a target to become carbon-free and fossil-fuel independent by 2030. The project was officially announced in 2012 ahead of the World Conservation Congress, which Jeju hosted that same year.

One of the first steps taken under the CFI initiative was the development of the world’s largest smart grid and microgrid demonstration complex to test renewable energy technologies, electric vehicles, and smart network systems. Successful procurement and demonstration of these technologies provided a solid foundation for Jeju to position itself as a carbon-free island. Jeju’s status as a special self-governing province enabled greater flexibility in policy reform, which was a key enabler in the application of advanced carbon-neutral technologies.

The CFI Jeju 2030 initiative was introduced globally at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris (COP21) in 2015 and received the P4G Energy Sector State-of-the-Art Partnership Award at COP26 in Glasgow in 2021. The project has since expanded across the island and holds strong potential for replication in other regions, particularly in developing countries. Jeju is also developing a green hydrogen ecosystem with support from central government ministries—namely the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy and the Ministry of Environment—along with large corporations, presenting significant opportunities for market expansion.

Initiatives such as Korea’s first green hydrogen production test site, the expansion of electric vehicle deployment, and the development of hydrogen-powered mobility projects not only contribute to emissions reduction but also generate new employment opportunities and serve as a driver of green economic growth. Through international partnerships and recognition, the CFI Jeju project continues to foster global collaboration in pursuit of carbon neutrality.

Although the initiative requires a long-term effort—from planning to the validation and presentation of carbon mitigation and trading data at the international level—its distinctiveness lies in the leadership of Jeju’s autonomous government, which has shown unwavering commitment to its realization. Supported by the Korean central government in research and development, emissions reduction in aviation and maritime sectors, and initiatives to limit vehicle registration, the prospects of Jeju achieving its 2030 zero-emissions target are increasingly promising.

As a UNESCO Global Geopark, this effort aligns closely with the 16 core development focus areas of geoparks, positioning Jeju as a leading global model in climate change mitigation and adaptation. Moreover, the active participation of local communities in preserving both terrestrial and coastal ecosystems further strengthens Jeju’s standing as a flagship geopark within the global network. With this strong portfolio, it is no surprise that Jeju frequently hosts international events on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and climate-related agendas, offering participants the opportunity to experience firsthand how Jeju’s sites serve as replicable models for other nations.

Why don’t we make a carbon Free Island in Indonesia?

Designated as a UNESCO Global Geopark in 2021, Belitong Geopark serves as a representative model of Indonesia's island geoparks. Covering an area of 4,883 km² and home to a population of 324,240, Belitong is categorized as a geopark with relatively low population density. Its distinctive geological features, rich biodiversity, and unique maritime culture serve as core strengths in shaping Belitong’s identity and branding as an island geopark.

Strategically located between two major Southeast Asian powers—Singapore and Jakarta—Belitong possesses a significant geographical advantage in terms of accessibility. However, this advantage has yet to be fully optimized, particularly by both local and central governments, to promote Belitong as an island of international standing. Situated at the tip of the Asian peninsula and endowed with valuable mineral resources, particularly tin, Belitong's strategic position is one of its key assets. Additionally, its geographic location has endowed the island with remarkable natural landscapes, including widespread granite TOR throughout its northern and southern regions.

There are several reasons that Belitong can become a strong candidate to follow Jeju Island’s success in becoming a Carbon-Free Island. One notable reason is its low population density—only 67 people per km²—allowing the preservation of its terrestrial and coastal ecosystems. This translates into a high carbon sequestration potential, supported by the well-maintained quality of its ecosystems. Furthermore, the island currently lacks large-scale industrial activities, thereby minimizing emissions of black carbon, a major contributor to atmospheric pollution. Belitong’s air quality index generally ranges from 15 to 45, falling within the “healthy” category. This presents a compelling case for local and central governments to prioritize development strategies aligned with sustainable development goals by integrating environmental, social, cultural, and economic dimensions.

Additionally, we have identified an opportunity to transition from an extractive economy to a more sustainable practice. Historically, Belitong’s economy has been reliant on extractive and destructive mining activities. However, the establishment of the geopark presents a turning point, enabling local authorities to explore sustainable economic sectors, such as tourism, fisheries, and creative industries, which can serve as long-term economic pillars for the island.

This opportunity should be seen as a strategic advantage for potential investors. Investor contributions to business development will support the achievement of sustainability targets. As such, prospective investors should ideally represent businesses operating within the realm of sustainability and aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Carbon Trading Potential in Belitong UNESCO Global Geopark

Belitong holds significant potential as a center for ecosystem-based carbon trading, supported by its well-preserved coastal and terrestrial biodiversity. The island features three main types of forests that serve as natural carbon sinks—primary, secondary, and production forests—with a combined area that exceeds the carbon sink regions of Jeju, South Korea. Its carbon absorption capacity is further enhanced by coastal ecosystems, particularly mangrove forests spanning 19,131 hectares. These mangroves, with a density of up to 1,500 trees per hectare and comprising 10 species, are known to sequester carbon up to five times more effectively than terrestrial forests, according to NOAA. The estimated carbon stock from these blue carbon ecosystems is approximately 66,728,928 tons of CO₂.

This remarkable carbon stock sequestration potential makes Belitong a strategic area for sustainable carbon trading schemes, both nationally and globally. Harnessing this potential can not only advance climate change mitigation efforts but also open up green and blue economic opportunities through carbon incentives. These incentives can be directed toward improving local community welfare, such as the development of conservation-based ecotourism, the empowerment of coastal communities, and the funding of nature preservation programs. By preserving its ecosystems and leveraging its carbon potential, Belitong can become a highly competitive island model that balances economy, ecology, and social well-being.

Blue Carbon Trading Policy and Regulation in Indonesia

Indonesia has taken strategic steps in developing policies and regulations related to carbon trading, including blue carbon, as part of its efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and achieve carbon neutrality. This is marked by the issuance of Presidential Regulation No. 98 of 2021 on the Implementation of Carbon Economic Value, which serves as the legal foundation for the national carbon trading system. This includes mechanisms for carbon certificate pricing and the establishment of emission baselines. Currently, the regulation is under revision to align with evolving needs, institutional authorities, and the complex nature of carbon economic value management.

In 2023, Indonesia officially launched its domestic carbon exchange and is set to open access to international carbon markets—particularly in the energy and forestry sectors—starting in early 2025. Additionally, since 2023, Indonesia has partnered with the World Economic Forum to accelerate blue carbon restoration and marine conservation programs.

Indonesia possesses rich blue carbon ecosystems with immense potential for development under carbon trading schemes. Its mangrove forests, covering approximately 3.36 million hectares, store over 3.4 billion metric tons of carbon, contributing about 17% of the world’s total blue carbon stock. Meanwhile, its seagrass meadows hold up to 83,000 metric tons of carbon per square kilometer. The economic potential of these ecosystems is substantial, with mangrove forests valued at over USD 90,000 per hectare. These ecosystems are not only ecologically critical but also present opportunities to enhance coastal community livelihoods through conservation and restoration activities.

Indonesia’s geoparks also play a significant role in supporting both blue and terrestrial carbon trading. For instance, the Ciletuh-Palabuhanratu Geopark in West Java features expansive coastal and forest landscapes with strong carbon sink potential. Likewise, the Belitong Geopark contains nearly one-quarter of its total island area in mangrove forests. By integrating sustainable geopark management with carbon trading initiatives, Indonesia can not only meet its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) targets but also generate green employment opportunities and foster local ecological-based economic development.

Nevertheless, challenges remain, particularly ecosystem degradation driven by human activities such as land conversion and pollution. Serious efforts are needed in ecosystem mapping, restoration, and data-driven monitoring to ensure carbon trading operates credibly and equitably. With a strong policy framework and abundant ecosystem potential, Indonesia is well-positioned to become a global leader in equitable and sustainable blue carbon trading.

Local Community Capabilities Development

Local and Indigenous communities in geopark areas play a central role in preserving blue carbon ecosystems, such as mangroves and seagrass beds. As long-standing custodians of their living spaces, they possess deep and holistic local knowledge of coastal ecosystem cycles. Within the geopark framework, recognition of this traditional knowledge serves as a powerful component of community-based conservation strategies. Their active participation extends beyond the physical protection of ecosystems to include educational roles—such as serving as environmental education guides, managing ecotourism ventures, and innovating local products based on sustainable resources.

This is where the value of collaboration between modern science and traditional wisdom becomes clear—not only in protecting nature but also in ensuring that environmental conservation is rooted in social and cultural relevance. The Global Geoparks Network (GGN) emphasizes three core pillars: conservation, education, and sustainable economic development. In the context of Indonesia—a nation rich in biodiversity and cultural diversity—these pillars are highly relevant for strengthening community involvement in blue carbon management.

Conservation programs that focus solely on preservation without integrating community welfare risk generating social conflict. On the other hand, by making local communities part of the solution—through initiatives such as community-based mangrove restoration programs, strengthening marine-based MSMEs (micro, small, and medium enterprises), and engaging youth in research and scientific tourism—conservation goals can align with efforts to improve livelihoods.

From a more critical and visionary perspective, the geopark approach should not merely serve as a branding tool for eco-friendly tourism, but rather evolve into a transformative model for ecological and socially just regional development. Moving forward, geoparks must be empowered to become community-based green economy incubators, where blue carbon trading projects are implemented transparently, equitably, and with the local community as the primary beneficiaries. This includes transparency in carbon stock recording, fair distribution of financial benefits from carbon offsets, and formal recognition of Indigenous-managed areas within national carbon policies.

Thus, geoparks become not only natural sanctuaries but also pillars of ecological justice that advocate for marginalized communities. This approach repositions communities not as objects of development, but as agents of change. In a world increasingly driven by global climate agendas, the geopark model—grounded in participation and justice—can offer an alternative development path that bridges global ecological interests with the basic needs of local communities: a lasting symbiosis between people and nature.

How can We Collaborate to Promote Blue Carbon Economies in Geoparks

Collaboration between the government, private sector, and local communities is the cornerstone of building an inclusive and sustainable blue economy ecosystem within geopark areas. The government plays a key role as both regulator and facilitator through supportive policies, such as Presidential Regulation No. 98 of 2021 on Carbon Economic Value and the launch of the national carbon exchange, which together provide a legal framework for blue carbon trading and green investment in coastal regions. Additionally, the government can offer fiscal incentives and capacity-building programs to empower communities in sustainably managing marine resources.

The private sector, on the other hand, brings investment power and technological innovation into this ecosystem. Companies can participate in mangrove restoration projects, marine energy development, and ecotourism through Public-Private Partnership (PPP) schemes—while upholding the principles of transparency, ethics, and sustainability. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) should not merely serve as a branding tool, but must genuinely support local community empowerment and environmental protection.

Local and Indigenous communities play a crucial role as stewards of the coastal ecosystems they have preserved for generations. Involving them in decision-making and coastal area management—through fisher cooperatives, coastal farming groups, or community-based carbon trading schemes—will foster a strong sense of ownership and enhance economic self-reliance. Initiatives such as training in environmentally friendly marine aquaculture, seafood processing, and educational tourism based on local culture offer pathways to integrate conservation with community welfare.

The synergy between these three actors represents a transformative force in establishing equitable and sustainable ocean governance. Collaborative models such as community-based conservation zones, blue carbon trust funds, and the development of coastal geoparks as living laboratories for the blue economy serve as tangible examples of effective collaboration. Such efforts must continue to be promoted to enable Indonesia to fully harness its marine potential as a source of national prosperity while contributing to the global climate agenda.

An image of a salt marsh, and example of Blue Carbon Ecosystem.

Tri Wibowo

Tri Wibowo is an International Law graduate from Universitas Diponegoro and currently serves as a Research Assistant at the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries, Republic of Indonesia. His work focuses on international maritime law, ocean conservation, marine spatial planning, and international cooperation. Passionate about environmental protection, he is expanding his expertise in blue carbon ecosystems and carbon trading. At GIAC, Tri acts as the Principal Advisor for Carbon Trading and Climate Solutions, leads Public Policy and Geopolitics initiatives, and supports People Strategy. He also contributes as a Research and Development Support officer for the United Nations Association of Indonesia. Prior to his role at GIAC, Tri was involved in the Belitong Geopark Youth Community (BGYC) for four years, where he contributed to research and development initiatives integrating geological heritage, biodiversity, and cultural heritage, as well as community development around the Belitong UNESCO Global Geopark. In 2021, he was selected to represent Indonesia at the 1st UNESCO Global Geoparks Youth Forum in Jeju Geopark, Republic of Korea.